From the high-profile arrest of Rudy Kurniawan in March 2012, to the recent arrests of several individuals accused of faking €2 million worth of Domaine de la Romanée-Conti wine, counterfeit wine is perhaps the defining issue for the fine wine industry in recent years.

The issue is not new, of course. Controversies surrounding wines from Hardy Rodenstock , as recounted in Benjamin Wallace’s page turner The Billionaire’s Vinegar, date back to the 1980s. Yet the more recent expansion of the fine wine market into China have increased the opportunities and incentives for wine forgeries, as highlighted by the recent series of articles by Nick Bartman on Jancis Robinson’s Purple Pages (3 out of 5 articles for subscribers only). An unofficial estimate by French publication Sud Ouest (subsequently reported on by others) estimated that 20% of the market for fine Bordeaux and Burgundy consists of fake wine. Though the estimate seems rather high, it’s another indicator of a widely-recognised problem.

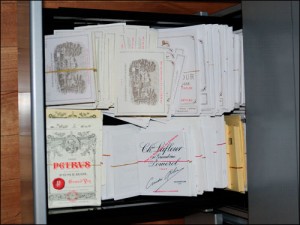

If there was a sure-fire way of detecting the fakes then of course the problem could be eradicated and wealthy connoisseurs could sip their Pétrus and sleep easy. A recent technical development in the scientific quarter of the Vinosphere might suggest we are closer to this becoming a reality.

A team at California’s Los Gatos Research led by Manish Gupta has developed a machine capable of analysing the isotopes contained within wine to determine whether it has been adulterated. It can also determine the origin and age of the wine. Crucially, Gupta’s team have developed a machine able to do this at a much lower cost than previously possible – $45,000 per machine rather than $200,000.

The problem being that if we open the bottle to test the wine then it’s too late; if it’s genuine you’ve already killed it. Enter the Coravin, a device that claims to allow users to take samples from bottles without removing the cork. If the sales literature is correct, this would allow a small but sufficient sample to be taken from a suspect bottle without ruining the precious fermented grape juice.

Yet even if all the above is correct, the testing is still not perfect. An isotopic analysis could only go so far in verifying whether the liquid in the bottle matched the text on the label – for example, it could narrow it down to appellation but not vineyard. For the time being this technology appears to be a useful tool but not a panacea. The role of actual human experts such as wine-sleuth Maureen Downey seems secure for the time being. But at heart, didn’t we all know that wine is far too subjective and to allow, dispassionate cold science to have that final word…?

Kurniawan’s trial is set to start next Month in New York (though reports last week suggest he may claim to be mentally unfit for trial) and is set to be a suitably dramatic occasion, generating even more headlines about the world of counterfeit wine. In the meantime, it’s incumbent on the wine trade to retain a cool-headed critical approach to fine and rare wines that could be too good to be true.